Lawrence of Arabia: How Peter O'Toole made the mirage real.

Where ordinary desert movies follow well-trodden tracks that lead nowhere, this epic blows through like a hot wind, reshaping every dune around its own path. Even the heat shimmer seems to have turned up with an Equity card.

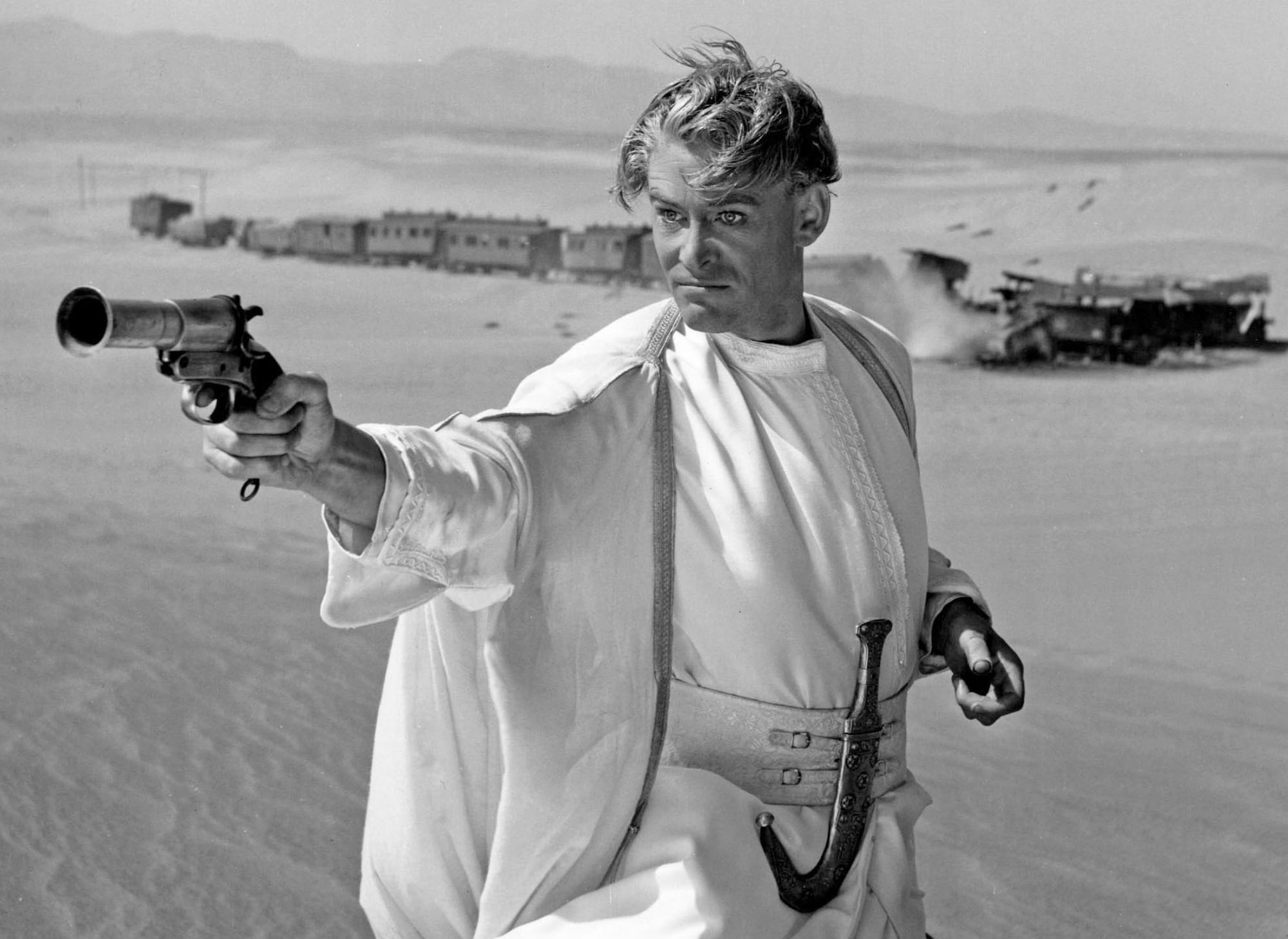

David Lean’s 222-minute masterpiece could so easily have been another stiff-upper-lip postcard from the Empire. Instead, it’s possessed by a tall, pale Irishman with eyes the colour of chipped Wedgwood, who proceeds to detonate every tidy notion of what a war hero is supposed to look like. And that — that — is the unpredictable something a first-rank actor brings to a role: the element you can’t storyboard, the jolt that makes the audience lean forward long before the camel appears on the horizon.

Casting roulette: how the accidental icon was dealt

The legend goes that producer Sam Spiegel tried to bag Brando, flirted with Albert Finney, and finally noticed a gangly 28-year-old in The Day They Robbed the Bank of England. Noel Coward quipped that if O'Toole had been any prettier, the film would have had to be retitled Florence of Arabia - and for once the punchline isn't exaggeration (empireonline.com). That near-miss casting carousel matters because it underlines how fragile greatness can be. Shuffle the deck differently, and the film is merely competent. Deal O'Toole, and suddenly Lean is working with unstable dynamite.

Eyes like lit matches

Roger Ebert called him "lanky, almost clumsy… with a beautiful sculptured face", a performer whose voice hovers "between amusement and insolence" (rogerebert.com). Nothing about that description screams conventional leading man, yet it explains why the camera can't leave him alone.

When Lawrence blows out a match and Lean smash-cuts to the birth of the sun over the dunes, our pupils are already primed: they've spent the previous minutes tracking O'Toole's glacial blue stare, the way it promises mischief one second and martyrdom the next. The transition from flickering flame to blazing desert is the movie tipping its hand, declaring that we're inside the head of a man who will happily set himself alight for an idea.

When Lawrence blows out a match and Lean smash-cuts to the birth of the sun over the dunes, our pupils are already primed: they've spent the previous minutes tracking O'Toole's glacial blue stare, the way it promises mischief one second and martyrdom the next.

"Nothing is written" (except when he rewrites it)

Take the rescue of Gasim. Every seasoned Bedouin insists the lost man is expendable; Lawrence wheels his camel and rides back anyway. Lean cross-cuts between boiling sky and blanched sand until O'Toole re-emerges, skeletal and victorious, rasping "Nothing is written." Empire's Angie Errigo calls it "eight minutes of genius," precisely because the actor sells the madness behind the gallantry (empireonline.com). You can sense the adrenaline flooding him and the secret thrill: a reckless boy realising he can bend fate if he feels like it. The line isn't noble - it's narcotic. Without O'Toole's volatile charge the moment is merely heroic; with him it becomes a manifesto for self-mythology.

Unbuttoned mythmaking

Lean's widescreen canvas is grand enough for three epics, but what keeps the thing aerated is O'Toole's refusal to play stable genius. Ebert spots the gleeful voguing atop the derailed Turkish train, half victory dance, half fashion shoot, and notes how the other characters barely react (rogerebert.com). It's not camp for camp's sake - it's Lawrence road-testing personas like costumes, bluffing entire tribes into unity by sheer theatrical bravado. That's the unpredictable dividend great actors pay: the sense that they're making it up on the fly and somehow dragging history along in their wake.

Charisma with hairline cracks

Peter Bradshaw, revisiting the 70 mm re-release, labelled O'Toole "a Valentino for the 1960s" and marvelled at how comfortable he is with the character's sexual ambiguities (theguardian.com). Watch closely and you'll see the edges fray – momentary flinches of self-disgust after the massacre at Tafas, or that brittle half-smile when a British officer tries to domesticate him back into khaki. The performance keeps pivoting between longing and repulsion, grandeur and shame. It's like watching mercury rolled across a hot plate: you can predict the physics but not the shape it will take.

Sounding the depths of silence

For all the quotable lines, the real sorcery happens in the hush. The first time Sherif Ali materialises out of the mirage, Lean holds wide, daring us to find meaning in emptiness. O'Toole does the same trick internally. He'll pause just a beat too long before replying, forcing us to fall into the silence with him. That negative space is where the character's contradictions breed: masochist and messiah, imperial agent and anti-imperialist. Lesser actors broadcast thoughts; O'Toole withholds them, and the audience supplies the electricity.

Risk as performance ethic

O'Toole's own career became a testament to betting on livewire choices - Becket, The Ruling Class, even Caligula when the gigs got weirder. But nowhere is the gamble cleaner than here: a relative unknown anchoring a four-hour epic with no conventional love interest and a desert bigger than most countries. The Empire essay reminds us the shoot itself ran longer than Lawrence's real campaign; a lesser performer might have been swallowed by the sandstorm. (empireonline.com)

That elusive "something"

So what is this something we keep circling? It isn't merely range or technique – though O'Toole had both. It's the ability to combust in ways even the script can't predict, to risk looking ridiculous and end up rearranging the audience's molecules instead. It's why we remember how Lawrence rescues Gasim rather than whether he succeeds, why the simple image of white robes against infinite ochre feels wired with possibility. In acting, as in alchemy, there's a moment when the ingredients stop being logical and start being legend. Peter O'Toole crossed that threshold and left the door ajar for the rest of us to gape through.